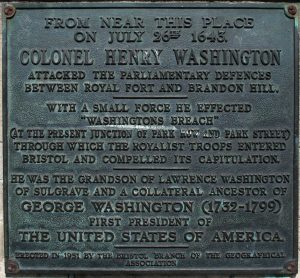

Leaving the Red House on Park Row just after 2pm we walked first towards the Museum and Art Gallery in Park Row to the first Civil War point on the walk. On the wall between the Museum and Browns the bronze plaque commemorates an event on 26th July, 1643 during the Civil War.

Crossing Queen’s Road in a south-westerly direction past the junction of Park Row and Park Street, the site of “Washington’s Breach”, a short distance down Park Street we found an insignificant marker in the pavement marking the route of the St John’s Conduit. From the ‘About Bristol’ web-site we learn that “the spring feeding it rises on Brandon Hill, and the system was constructed by the Carmelite Friars. The water travels under Park Street and the Centre through pipes, cisterns and tanks. During the aftermath of Second World War bombing raids, this tap was the only source of water available in the old city area”, the conduit issuing near St John’s church. “It has been moved from its original position inside the walls.” [To a position in Quay Street.]

From there we accessed Brandon Hill via Charlotte Street and swung left- and then right-handed to climb up around the hill with Cabot’s Tower looming over us. It was noted that the site of St Brandon’s Chapel is marked on the Bristol Corporation ‘Know Your Place’ [‘KYP’] web-site to the east of the tower and that ‘Brandon’ is believed to be cognate with ‘Brendan’. There is a St Brendan’s school in Bristol, and because of the medieval manuscript describing his voyages he is sometimes known as ‘St Brendan the Navigator, and is thought to have reached and returned from North America some time in the first third of the sixth century, well before the Norse Erik the Red. The journey was reputed to be made in a curragh style boat 36 feet long and 8 feet in the beam with a covering of ox-hides, and in 1976-7 Tim Severin made the journey in a replica and proved the feasibility of the journey as well as identifying some of the places described in the story. It is not known if the connection with this early navigator was the reason Brandon Hill was chosen for the site of the Cabot Tower or whether it was purely fortuitous.

This brought us to the substantially well- preserved, somewhat restored and now something of a park feature, bastion of the Civil War fortification on the crest of the hill. The wall continues to the south some way down the hill, fronted by a substantial ditch, and can be followed inside its route down a very irregular set of steps. Discretion suggested we took an easier path downhill on the outside. Another bastion site is shown on ‘KYP’ towards the bottom and we were satisfied that we had positively identified it. The presence of WW I practice trenches, further up the hill were mentioned as we went towards the steps down to Jacob’s Wells Road opposite the foot of Constitution Hill.

From the vantage point of the steps the site of the possible ‘Mikveh’ across the road was clear, then about 100 yards uphill, we looked across to Gorse Lane to be told about the identification of an 18th century plunge pool which had initially been interpreted as a cellar. Now thought to be under the ochre coloured house it was originally on the boundary of an estate which ran up over the hill into Clifton. Apart from the one inside the Georgian House it is understood to be the only outside one known in Bristol and it had been declared that it should be preserved in situ. The stonework was finely dressed ashlar with tongues on two edges and grooves on the other two, presumably to help with stability but also to increase the leakage path through the stonework. There was a drainage pipe in the bottom against the wall, and presumably the pool had been fed from a spring further up the hill. A very unprepossessing plate in the pavement in front of the lane’s name-board was apparently access to another medieval conduit which ran down under Jacob’s Well Road feeding the Abbey precinct and possibly across College Green. It ran in an open trough on the floor of a tunnel which was in the form of a narrow gothic arch. There was a settling tank in the middle of the road at the junction with Constitution Hill, before continuing down towards Anchor Road and the Abbey church and precincts. There was further information in one of the Temple Local History Group publications.

On the way down the road towards the Anchor Road/Hotwells Road roundabout an inscribed ‘P’ was seen on one of the kerbstones and it was remarked that other symbols may be found on these old kerbs. Possibly some form of quality control or piece-work measurement but their actual purpose has not been determined. Turning into Anchor Road and finding we were in the middle of some sort of local community event so distracted our guide that it was not until the ‘Norman Arch’ beside the library that he remembered that across the road towards the dockside from the roundabout there had been a lime kiln, and also a glass-house owned by Lucas who went on to found that at Nailsea.

The Norman Arch was the entry to the medieval Abbey precinct. A potted history of the Abbey followed. Founded around 1140 by the first earl of Berkeley, the most significant thing is its claim, in some sources, to be the finest example of a hall-type church, where the side aisles are the same height as the nave. There are varying thoughts as to whether it was the prototype which was subsequently copied in Europe, or whether it was the first in Britain to be copied from Europe. The other thing to note is that everything from the crossing westwards was constructed late in the nineteenth century. Henry VIII turned the Abbey in to the Cathedral, which is well worth a detailed visit in its own right. At present a detailed guide book is not available. In passing, John Hunt mentioned that the remains of a circular dovecote in what was the south-eastern corner of the Abbey precinct, had been found during extension work for the Cathedral School.

Crossing the head of St Augustine’s Reach where the River Frome runs into the floating harbour to the east side of Broad Quay it was pointed out that a later extension of the city wall ran down the line of the quay and that there was a tower across the road near the water feature. A member of the group asked what had happened to the statue of Brunel which stood in that vicinity, but its fate was not known. From ‘KYP’ the Water Gate site was in the vicinity of the southern bus shelter. At the end of Marsh Street was the site of the Marsh Gate as the area to the south and east was called “The Marsh”. Similarly the area now the site of @Bristol and around was ‘Canons’ Marsh’. The old pump in the courtyard of the Merchants’ Almshouses at the start of King Street was indicated but some eyes were more drawn by two bikini-clad young ladies taking advantage of the sunshine. Moving swiftly on there is a coat of arms, presumably of the founder, on the gable wall. What is now a Chinese restaurant was the Old Library, and ‘KYP’ shows a Marsh Wall tower stood in what is now the front courtyard. The line of the wall is shown on a large-scale Ordnance Survey map as in line with the front of the building, and has been traced right through to the dockside opposite the Llandoger Trow inn and restaurant. Gundula Dorey told us that a tower has been identified behind the St Nicholas Almshouses. [We had already passed the Theatre Royal, its frontage and entrance extensively remodelled several times, incorporating the Coopers’ Hall, and reputed to be the oldest continuously used theatre in Britain.]

The Llandoger Trow is possibly the setting for the Bristol inn kept by Long John Silver early in RL Stevenson’s ‘Treasure Island’, but more notably is where Daniel Defoe met Alexander Selkirk who was the model for ‘Robinson Crusoe’. Beyond lies Welsh Back where the trows from south Wales docked. Turning left took us up to the ‘Mercure’ hotel, formerly the ‘Brygstowe’. By courtesy of the reception staff there we were able to study the display case in the foyer. This contains some of the medieval artefacts found in water-logged deposits by the Avon Archaeological Unit when the foundations of the hotel were being excavated. Having crossed to the east end of St Nicholas’ church, looking across the High Street showed an almost pyramidal structure. This forms the entrance to medieval merchants’ cellarage preserved under the pavement. It was mentioned that it is thought that the line of the River Frome originally more or less followed the line of Baldwin Street from the Centre, before being diverted to its present course. We then turned left along St Nicholas Street, following the line of the earlier city wall to Corn Street which once ended at St Leonard’s Gate. The ‘nails’ outside the Corn exchange were remarked upon but not visited, and we crossed through yet another street fair to dive into the somewhat uninviting-looking [St] Leonards Lane, still following the walls, and noting parish markers high on the walls on the way through. These are recorded on a Temple Local History Group plan, but not on ‘KYP’.

We could not continue across through Bell Lane because of construction works, so turned out of Small Street past the site of St Giles’ Gate into Quay Street to St John’s Gate, and turned in under the arch to Broad Street. John Hunt recalled how he had seen an early photograph of the gate before the pedestrian arches on either side were constructed, as traffic could still use the gate within living memory. We could not proceed any distance along Tower Lane to follow the wall line as modern metal railings [a seemingly quite recent feature] have been erected across the path, so went a short distance up Broad Street to look into Tailor’s Court for its medieval atmosphere.

Retracing our steps to Quay Street we went to the right to look at St John’s Conduit Head. Keith Stenner, who has been doing voluntary work in St John’s, told us that there are plans to undertake some conservation work on the structure. From there we went along Christmas Street to cross Rupert Street. Turning left we were able only to look through the gates of St Bartholomew’s Hospital before turning up Christmas Steps. From Wikipedia: “The street was originally called Queene Street in medieval times before becoming known as Knyfesmyth Street, after the tradesmen there. The Middle English pronunciation of Knyfesmyth, with the K sounded, may be the origin of the street’s modern name. In the 17th century, the Christmas Steps is also believed to have been called Lonsford’s Stairs for a short period, in honour of a Cavalier officer who was killed at the top of the steps during the siege of Bristol in the English Civil War”.