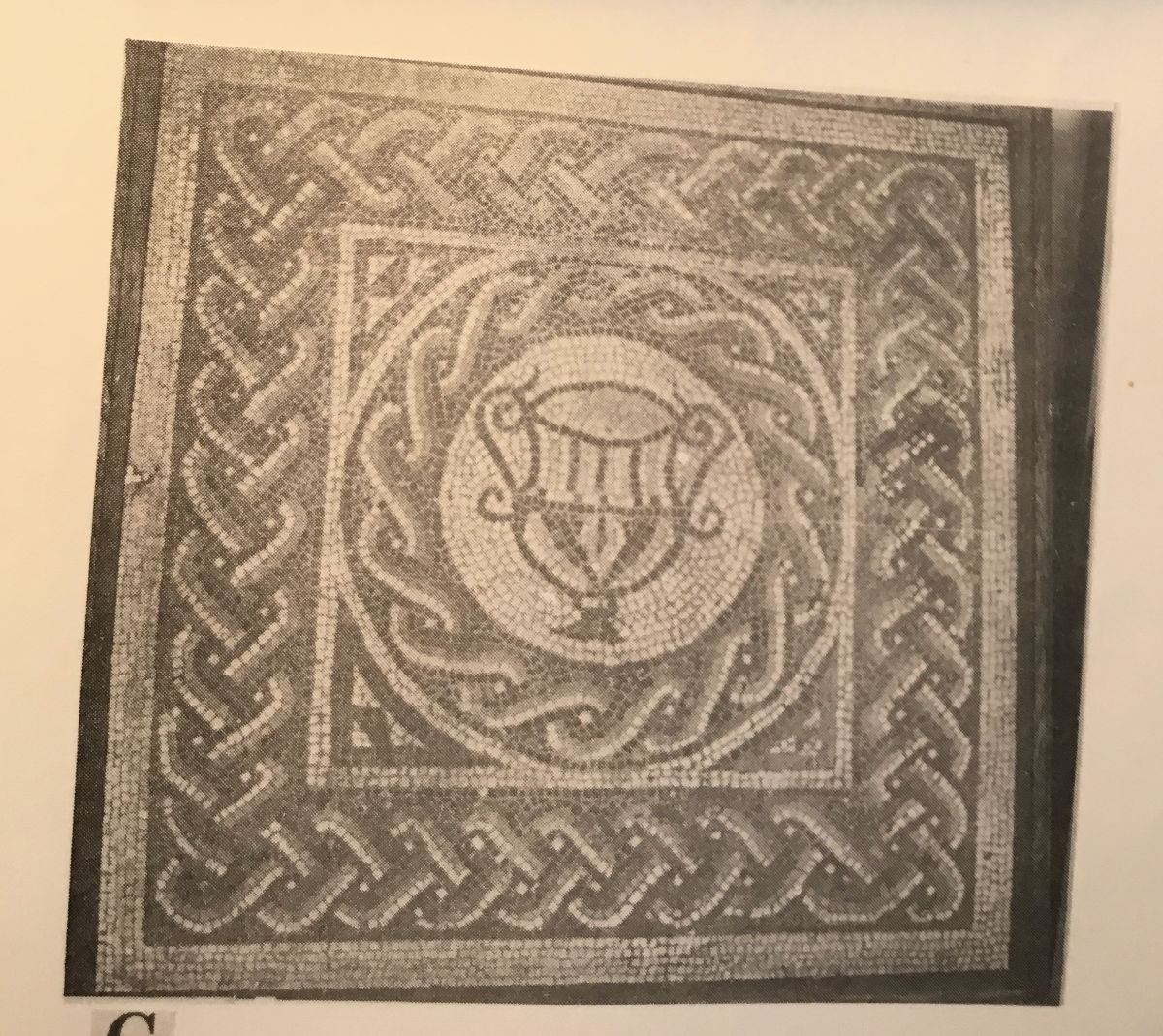

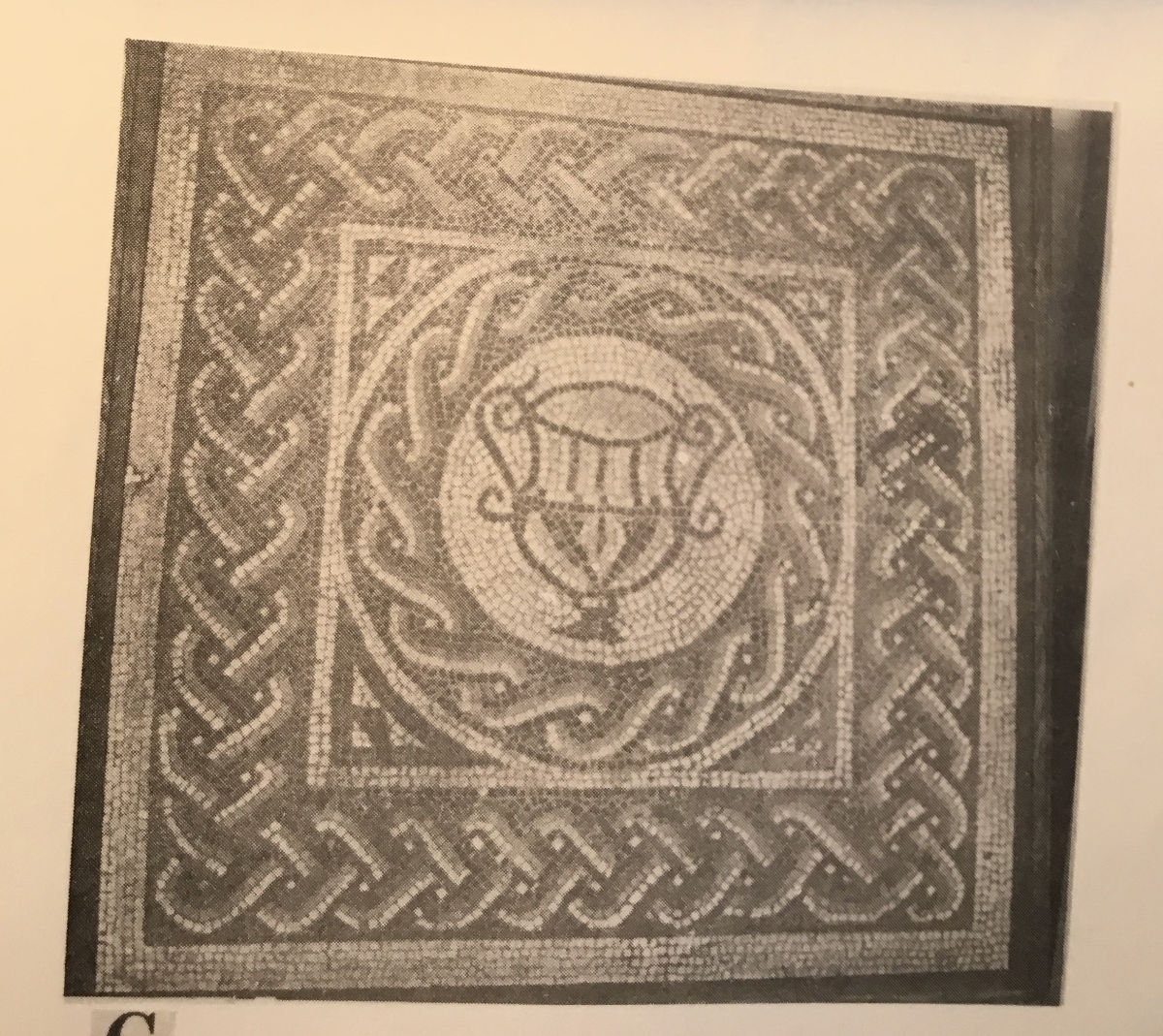

The talk started with showing that the Gatcombe site is located just to the west of Long Ashton village, very near to Bristol. Roman remains first came to light during the digging out of the deep cutting for the Bristol to Exeter railway in the early 1800s. Extensive foundations were uncovered, as well as a colonnade, a hypocaust tile and other evidence of a fine building. Sadly no proper archaeological excavation was carried out; only a few items survive in the Bristol museum such as a mosaic and a fine carved table.

Barry Cunliffe conducted the first professional excavation in the 1960s and established that a Roman settlement had existed in the first and second centuries. A larger excavation but only of the north-east corner by Keith Brannigan was reported in 1977. He revealed the remains of 24 buildings of which only two might have been dwellings. Those activities which can be postulated suggested light industries such as iron smelting, pewter vessel production, large-scale processing of grain. Over 4000 sherds of pottery were found. The largest amounts came from Dorset (mostly black burnished ware ), and the Congresbury kilns but a minority came from places abroad such as Roman Germany or southern Gaul.

Over 500 coins (dropped accidentally, not a hoard) underlines the commercial activity. It must be remembered that Brannigan only knew of the site North of the railway cutting. On the basis of all this, Brannigan proposed a villa, with the main house destroyed by the railway cutting and the other buildings contributing to the commercial side although he conceded it would have been the most unusual example of a villa with such massive defences.

The picture changed when in 2010 Bob Smisson’s geophysics work showed that the walls extend significantly south of the railway cutting, doubling the area enclosed to 14.5 ha. No Villa is remotely this size with such massive walls so Smithson proposed that the site should not be considered a villa but a small town, of which there are many examples in Roman Britain. These differ from the cities which are much larger and contain structures such as forums, basilicas, public baths , big temples. At the other end of the scale they cannot be described as rural villages because their buildings show some sophistication with rectangular multiroomed stone construction, tiled roofs, window glass, and their possession of light industries and workshops. In terms of size Gatcombe ranks among the biggest of small towns, yet is not generally recognised as one of them. I think this should change.

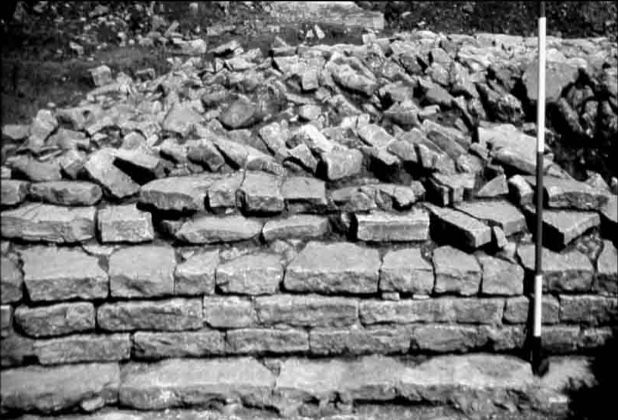

The walls of the Gatcombe site do pose problems: why walls at all and why so massive? They have been excavated in several places; only a handful of courses of regular stone blocks remain as a facing behind which a rubble core extends for 5 m (15 feet). (The reason so little survives, and this is true of the buildings as well, is that large amounts of stone were sold off to builders from Bristol). It is obviously reasonable to assume that walls are intended to defend against enemy attack. However there was no threat at the time of construction in the 270s A.D. Earlier, after the military pulled out of the south west and decommissioned their forts in the 70s and 80s A.D., there had been a profound peace in the area (Boudicca’s rebellion did not reach this far). No textual or archaeological evidence suggests trouble. But what about the Irish? Finds of Roman artefacts and goods through much of Ireland and even excavation of a probable Roman trading post near Dublin suggests peaceful coexistence for centuries after Claudius‘s invasion of 43 A.D. However as the Roman empire in the west began crumbling towards its end, Irish raiding did become significant, leading to damaged villas and eventual settlement in parts of south Wales and possibly Cornwall. Nevertheless Irish raids could not be the reason for building the walls because there is no contextual or archaeological evidence for them before the mid and late 300s, about 100 years after the construction of the walls. So perhaps we need to look for other motivation for constructing perimeter walls around towns.

The London Roman walls were built around 190–220 AD. There was no military threat at this time either within Britain or from abroad. A recent article in the journal Britannia states “freshly quarried stone (for the wall) suggests benefaction and civic pride“ and that the walls might be intended as “defensive or (an expression of) civic pride“. English Heritage says “defensive but also represented the status of the city “.

Mildenhall Roman town (called Cunetio) has town walls with 17 towers and a monumental Southgate, yet the area enclosed is small, only 6 ha. Being well inland between Bath and Reading, it feared no coastal raids from Irish or Saxons and certainly not from the distant Picts in the North. However, the date of the walls was a time of prosperity for the town which had become encircled by villas. Perhaps the local authorities wanted to express pride in their town, however small, and felt the need to catch up with other already walled towns. Our own Bristol also develops this idea. A recent book on Bristol proposes that “the function (of the walls) is debatable… A solely defensive purpose is questionable… Civic identity certainly a factor, clearly shown by rebuilding of the gateways in the walls in the 1730s, long after a defensive purpose had ended. The Marsh Wall could never have been wholly effective as a defence, but may have been wholly effective at making a statement of the importance and power of Bristol to mariners arriving at the quays“. Indeed to go further, some structures have no defensive purpose whatsoever, e.g. mock but realistic “castles“ built as homes such as Banwell Castle or Eastnor Castle or homes being built as castles even to this day. So, to sum up, it is suggested that the walls of Gatcombe were not intended for defence but to express civic pride and status. Some scholars support this idea in general, for example Kulikowski: “status competition (among third century cities Roman cities in Spain) is a plausible explanation for their construction… Walls with something new over which cities could compete“. Perhaps the Gatcombe Court walls were for show and to impress and not for defence.

There is another problem about Gatcombe’s walls: why were they so thick? They exceed the thickness of London’s town walls and even Hadrian‘s wall. If this was intended to emulate the walls other towns had built or were building at this time (as Kulikovsky proposes) then the temptation might be to build ever better and bigger. Pliny found this happening in Bithynia when the emperor Trajan sent him as his special representative. Two long–time rival cities, Nicaea and Nicomedia, were attempting to build better and bigger facilities – aqueducts, leisure centre, theatre – and were getting nowhere. It was Pliny‘s job to sort it out and is an early example of central government intervention in failing local authorities. Thus, it is plausible that Gatcombe Court was trying to outdo other places, perhaps nearby Bath where the walls were smaller, but whose buildings were very grand.

Was the building of town walls a State enterprise or did the initiative come from local authorities? The time span over which small towns received their walls is 160 years from the first to the last. If the state had felt there was an imperative for town walls it would hardly have taken them so long to implement. Then again, the plan of town walls reveals a wide range of shapes as local authorities made up their own minds, where state institution such as military forts, basilicas, forums tend to have a pretty uniform appearance. So both these considerations point to local authorities being the instigators of the wall building.

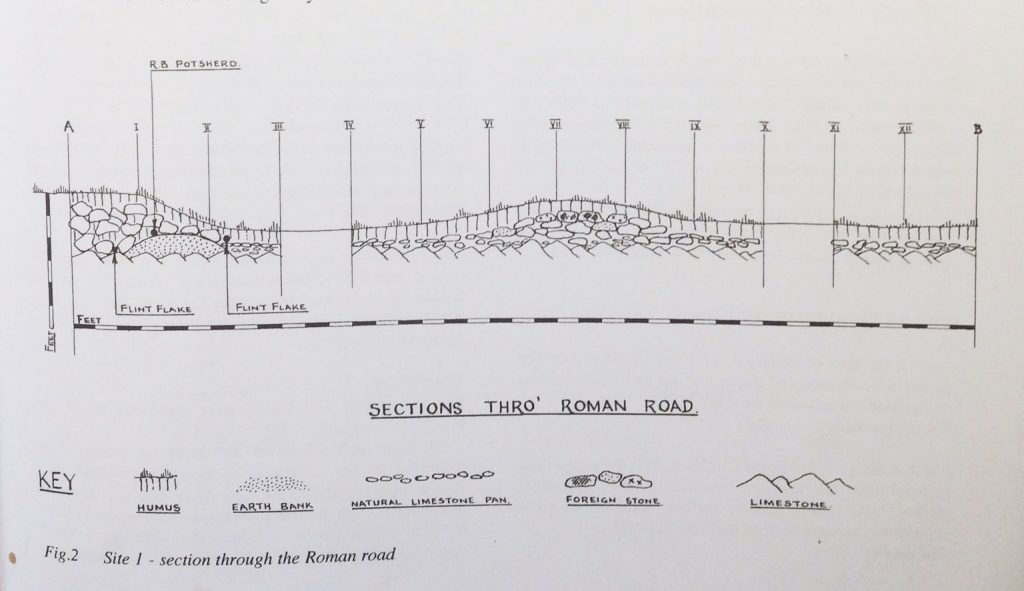

Who were these local authorities? Each province was divided up into local administrative units, each about the size of a large county and usually based on the largest pre-Roman kingdom or tribe in the area. The actual authority was vested in the local Senate also called an Ordo , composed of counsellors called Decurions who were the local (non-Roman) powerful and wealthy. A town must have communications yet Gatcombe has no roads shown on the Ordnance survey map (which usually shows Roman roads) and this apparent lack of roads has often been seen as a problem in understanding Gatcombe. A road to the north connecting Gatcombe and Sea Mills in Northwest Bristol (Roman name: Abona ) has long been proposed but not universally accepted – it appears in some maps but not others. There are, however, several clues. A clear “agger“ (a flattish convex road shape rising from each side of the road to a crown to enable rainwater run-off) can be seen just north of Gatcombe leading northwards towards the Ashton plantation. Somewhat further on in the village of Ashton Leigh on the A369 Bristol to Portishead Road, a short stretch of Roman Road pointing towards Sea Mills was excavated by Keith Gardner. Lastly a well engineered Terrace way has been identified which leads down to the river Avon along Paradise bottom near Leigh Court. Of course it has to cross the river. A ferry is possible, but a bridge is more likely.

Roman bridge technology was not matched until early modern times and could easily have coped with the tide ranges and mud of the river Avon. There is no trace of a bridge now, but evidence of a bridge in South Wales exists to carry the Roman road from Gloucester to Caerwent in south Wales over the River Wye at Chepstow. Wooden piles survive in the riverbed dated by radio carbon to the Roman period. The Wye and the Avon are almost opposite across the Severn estuary and experienced the same tide conditions and deep mud. Lack of traces in the Avon can be explained by the much heavier amount of seagoing ship traffic proceeding up to the port in Bristol and the consequent dredging.

As there is a road to the north from Gatcombe, it is not credible to think there was not a road in a southerly direction. A route is proposed proceeding from a gate in the walls south of the railway cutting that at first follows along a footpath by the small River Land Yeo and goes to a point near Barrow Court. One clue along the stretch is where the line is cut through at right angles by a small lane; rising above and on each side of the lane are relict aggers facing one another where the lane has cut through them. There is a gap after Barrow Court, but resuming the line in the woods around Goblin Coombe, it drops down to Iwood Manor (to the west of Congresbury) where geophysics has revealed traces of the road. Further on the line follows a long stretch of straight hedge rows finally pointing towards the newly discovered roadside settlement at Winthill just south of Banwell. Here a grand stretch of road has been uncovered. If, as seems likely, it joins with our proposed road network to the north, east, and north east where might it go to the south?

A road exists between Gloucester Roman city and Sea Mills/Abona. From there it extends to Gatcombe. There must be a connection between Gatcombe and the important new roadside settlement at Winthill, south of Banwell and we (the North Somerset Roman Road P roject) have proposed a route. To the south of Winthill there is no known Roman settlement for a long distance before the Ilchester Roman town is reached in Somerset. A Roman road runs roughly north-west from Ilchester in the general direction of Winthill and then turns sharply west, suggesting a possible Northwest continuation, which is taken up by a short stretch Roman Road at Street on the same line. It seems reasonable, therefore, to postulate a long distance Roman Road between Gloucester and Ilchester. At the latter it would meet the Fosse Way, the main route to the Southwest.

The last slide shown was titled “romanisation”. Traditionally that word brings to mind such things as grand public buildings and structures, villas, mosaics, literature and culture in general. All of course perfectly valid manifestations of “romanisation“. However, I wish to propose another level concerning the quality of life for a wider range of the population than just the elite. For example, it can include ordinary houses with multi room rectangular solid construction, tiled roofs and window glass and a greater chance to move around via greatly improved communications especially roads and in an environment of peace. There would be a greater variety and a medium range of every day goods that were produced by a vibrant economy together with a background of written legal process and at least some degree of local law enforcement (managed by the Civitas, overseen by the provincial governor); there would be a widespread (but by no means universal) supply of clean water and provision for sewage disposal. At this level of romanisation, small towns such as Gatcombe (an intermediate position between the fairly few cities and the great mass of purely rural and agrarian habitation) had an important part to play.