For our annual Grinsell Lecture, Prof. Horton began his talk by quoting Leslie Grinsell who stated that “….. archaeological methods are not likely to be practical when castles are inhabited”. Prof. Horton outlined and illustrated the findings of the University of Bristol’s training excavation and research project at Berkeley Castle since 2005, which showed that modern research methods could now show that the Berkeley site and surrounding landscape had been occupied continuously from Roman times until today.

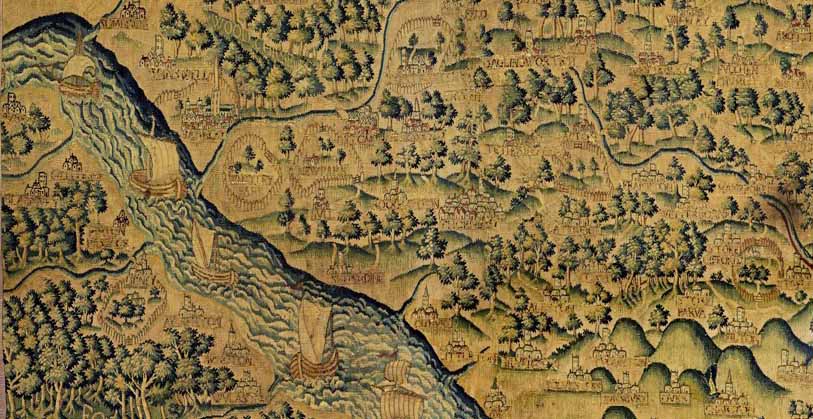

Berkeley sits on the Little Avon at the point of navigation, not unlike the location of Bristol. Berkeley was seen as a ‘mini-Bristol’ with similar ports and town layout. Sheldon’s tapestry map of Gloucestershire shows how ships could reach the port of Berkeley, i.e. sail up to the castle in the 1200s.

We were shown a slide of the chantry chapel of the Berkeleys inside Bristol Cathedral (formerly St. Augustine’s Abbey) and outlined the power and prestige that this family held not only in Berkeley itself, but across the country. The Berkeleys are the longest serving family in residence in a Medieval castle in England, having occupied the site since the 12th Century. Robert Fitzharding, the key person in Berkeley’s rise to prominence, came from Saxon stock and was Lord and Baron of Berkeley. He was an astute and effective businessman, trading with France, and financed Matilda’s bid for the monarchy against Stephen. Fitzharding was rewarded with large estates and permission to re-build Berkeley Castle in 1154.

Robert Fitzharding set up The Chapter House in St. Augustine’s Abbey and began building the Shell Keep, the Inner Ward and the Outer Ward at Berkeley Castle. The St. Augustine monks created a tide mill and engineered a complicated water management scheme.

Previous excavations at Berkeley were by the 8th Earl, who did some digging around the keep, but mis-interpreted the results. It was not until the University of Bristol’s project in 2005 took place, that some real discoveries were made. Excavations initially took place in Nelmes’s Paddock and Edward Jenner’s garden. Nelme’s Paddock was a palimpsest of kitchen gardens and some very early levels. Elizabethan coins from 1580s were recovered, together with clay pipes and drinking vessels. Moyle’s Map of 1544 shows the road to the castle and St. Michael’s Lane and this was confirmed during excavation. Civil War deposits show that in 1645 the Parliamentarians seized the castle, and a musket ball in the wall of the church still survives. A ditch had been dug to defend the church at this time. The project found the truncated square side of a huge square keep with a bailey behind it that was built by Fitzharding, in the area of the surviving keep.

A line of well preserved skeletons were uncovered close to the wall in Nelme’s Paddock which lay in a deposit between the civil war the 17th century kitchen gardens. They show scurvy in the children. Houses and burgage plots were also uncovered and ditches earlier than the Civil Wall. An 11th Century coin of William Rufus came from the paddock.

Three coins are known from the Berkeley Mint dating to 1055-7, as the castle sits on major Anglo-Saxon activity. Was Berkeley a burgh? In 759 the Berkeleys founded a minster, one of many in the Severn Valley and there are historical references to it. John Leland visited Berkeley in 1540 and noted “some say there was a nunnery”. But where was the monastery? The project believe it sits on the site of the castle, as stonework has been found during excavations in the form of a string course in the church. The project found the minster enclosure preserved in the Butterfly Garden of the Jenner House, together with a coin of Edgar (c. 959-73). In Nelme’s Paddock a knife handle, tweezers, an astel (page turner), whetstone and spindle whorls dated to c. 8-10th centuries were recovered. The 1862 gold ring found earlier at Berkeley and exhibited in Kensington in 1862, is of Anglo-Saxon design with filigree gold with inlaid red and blue glass.

To confirm the Anglo-Saxon presence further, a sequence of Sceattas (silver coins) were found in Nelme’s Paddock. These are rare, early Anglo-Saxon coins.

The Roman presence was found in the form of a Roman spoon and in the Jenner Garden a Roman skeleton, together with wall plaster that is comparable to that found at Frocester Court, Glos.

The Berkeley Castle site, therefore, can show a sub-Roman and Roman presence in its origins, which continued into the Anglo-Saxon period, before the influence of Robert Fitzharding enhanced its power and prestige in the early Medieval period.

This excellent talk for the annual Grinsell lecture not only showed the Bristol connection with Berkeley Castle, but highlighted the important findings and interpretations that have been revealed from the University of Bristol’s research project since 2005.